On the occasion of artists’ round birthdays and anniversaries of deaths, museums put on commemorating exhibitions. Since I started writing for this blog, I was lucky enough to happen upon three of this kind (see my posts Death in Trieste and Insights into Bruegel). Every one of these shows helped me widen my horizons a little bit more and sharpened my observational skills.

An Easter Surprise: Lehmbruck And Rodin In Duisburg

This was especially the case with the exhibition I visited during the Easter holidays, not far from home. Not only did I get the chance to meet again with the work of a favorite artist of mine, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), but at the same time I discovered a prominent sculptor I wasn’t at all familiar with, Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919). Happy to have come across this important German artist nearby, I went back another time a few days later.

On my first visit, I joined an exclusive guided tour offered by the TV-cultural magazine Westart. Their small, informative TV-report on the exhibition had made me curious. Besides, it is always exciting to win something. The art historian, author, and filmmaker Jörg Jung showed us around. By raising questions, he drew our attention to the similarities and, above all, the differences between the two outstanding artists. He invited us, again and again, to take a closer look and make our own discoveries and conclusions.

Learning To Look Closer

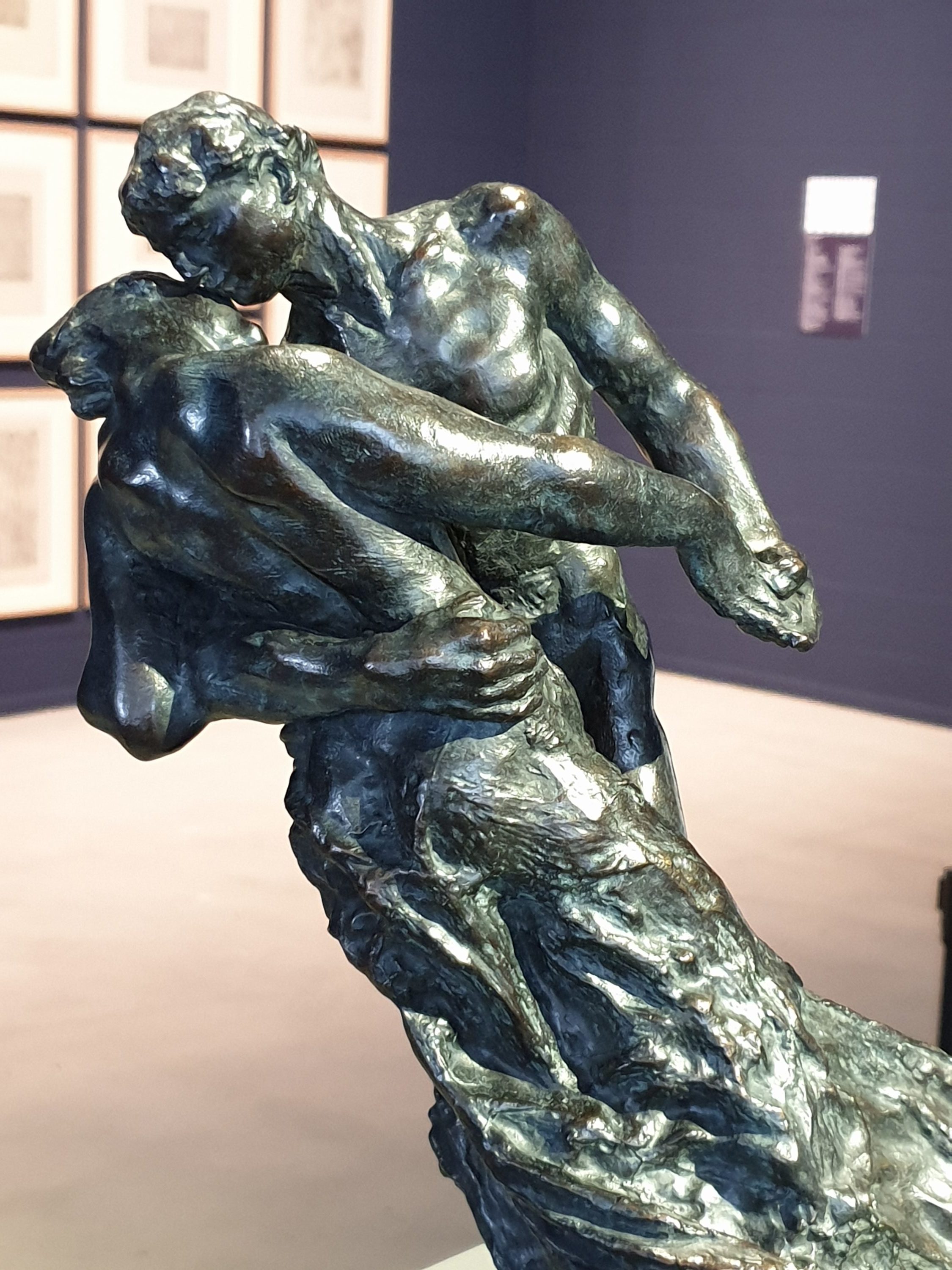

Thus encouraged, I noticed, for example, what difference the choice of material makes and how a sculpture’s more or less smooth surface makes it more or less classical in an academic sense. Auguste Rodin, in particular, loved to work very physically with his coarse hands, giving many of his works sensual movement and an unfinished impression. Wilhelm Lehmbruck, on the other hand, experimented a lot with different materials and worked towards carving out more introspection and spirituality in his objects. Both artists played with sculpture excerpts and torsos, always in search of “the essence”.

Sculpture is the essence of things, the essence of nature,

that which is eternally human.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck

Beauty is not a starting point, but a result;

beauty exists only where there is truth.

Auguste Rodin

Studying The Past Before Creating A Personal Style

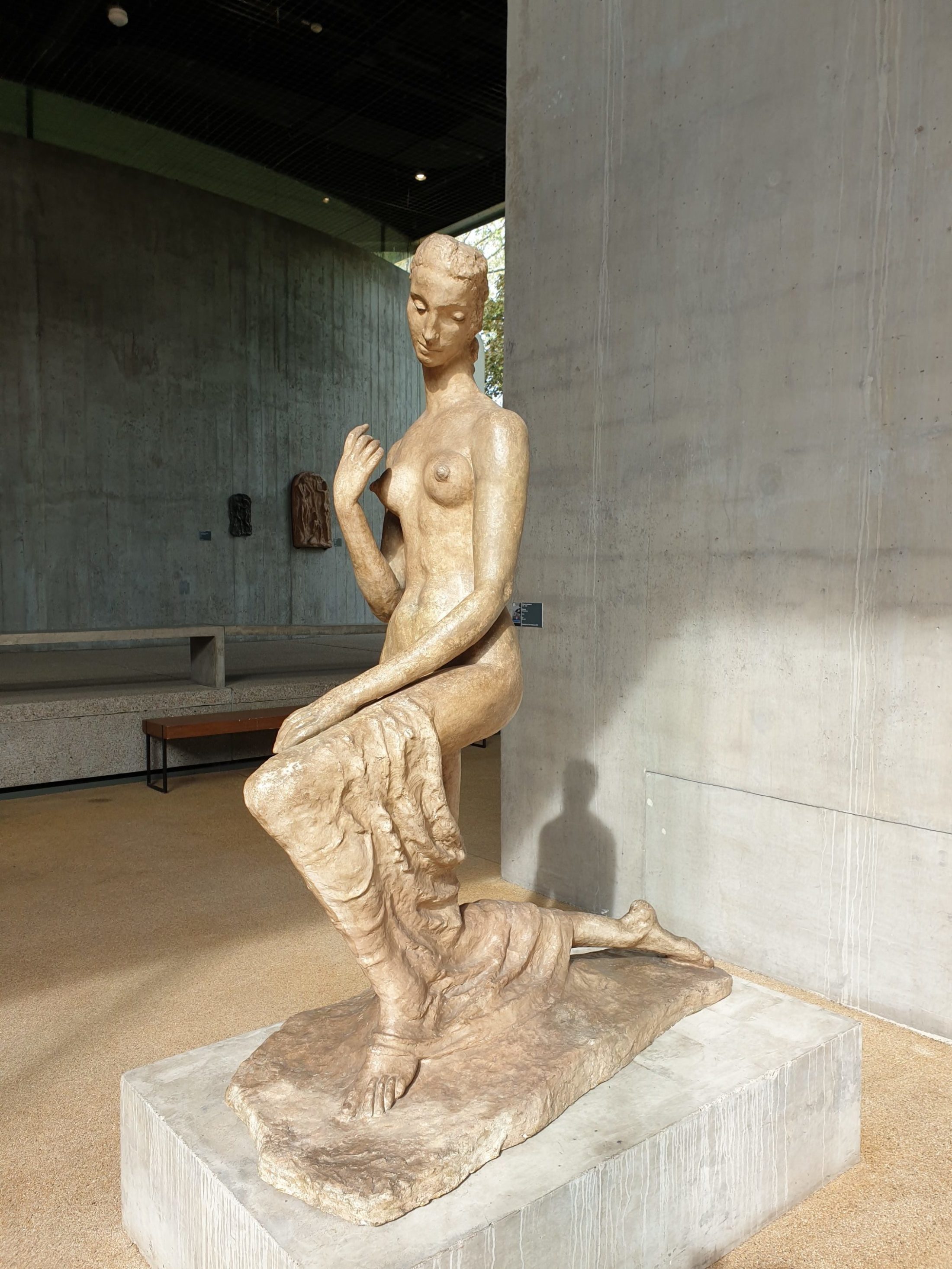

Our guide also drew our attention to the little innovations by which one can identify a young artist aiming to break with traditions, such as the undisguised body curves and folds in Lehmbruck’s first success, Bathing Woman (1902/05). The Academy of Fine Arts in Dusseldorf bought this work from its young master student and thus enabled him to go on a study trip to Italy. There he studied, among others, the works of Michelangelo, one of the greatest sculptors of all times. Michelangelo had also been a great inspirational figure for Rodin.

In general, art lives from the fact that artists study the past, learn to analyze it and develop their own style over time, depending on their talent and nature, as well as their environment and the time they happen to live in. All artists get to chose their subjects from the great basin of art iconography. We thus can admire how differently a story can be interpreted and cast or shaped into form.

But Who Was Wilhelm Lehmbruck? And What About Auguste Rodin?

Wilhelm Lehmbruck was born in 1881 to a coal miner’s family in a suburb of Duisburg. Not only was his talent discovered early, but he soon became a master student of the Academy of Fine Arts in Dusseldorf. He celebrated early successes that allowed him to live from his art, as well as to travel. One of his first travels led him to Paris, the capital of art at the beginning of the 20th century, where he couldn’t but visit the atelier of his idol, Auguste Rodin. But he immediately realized that he was looking for something else in art. Maybe Rodin and he were too different as human beings?

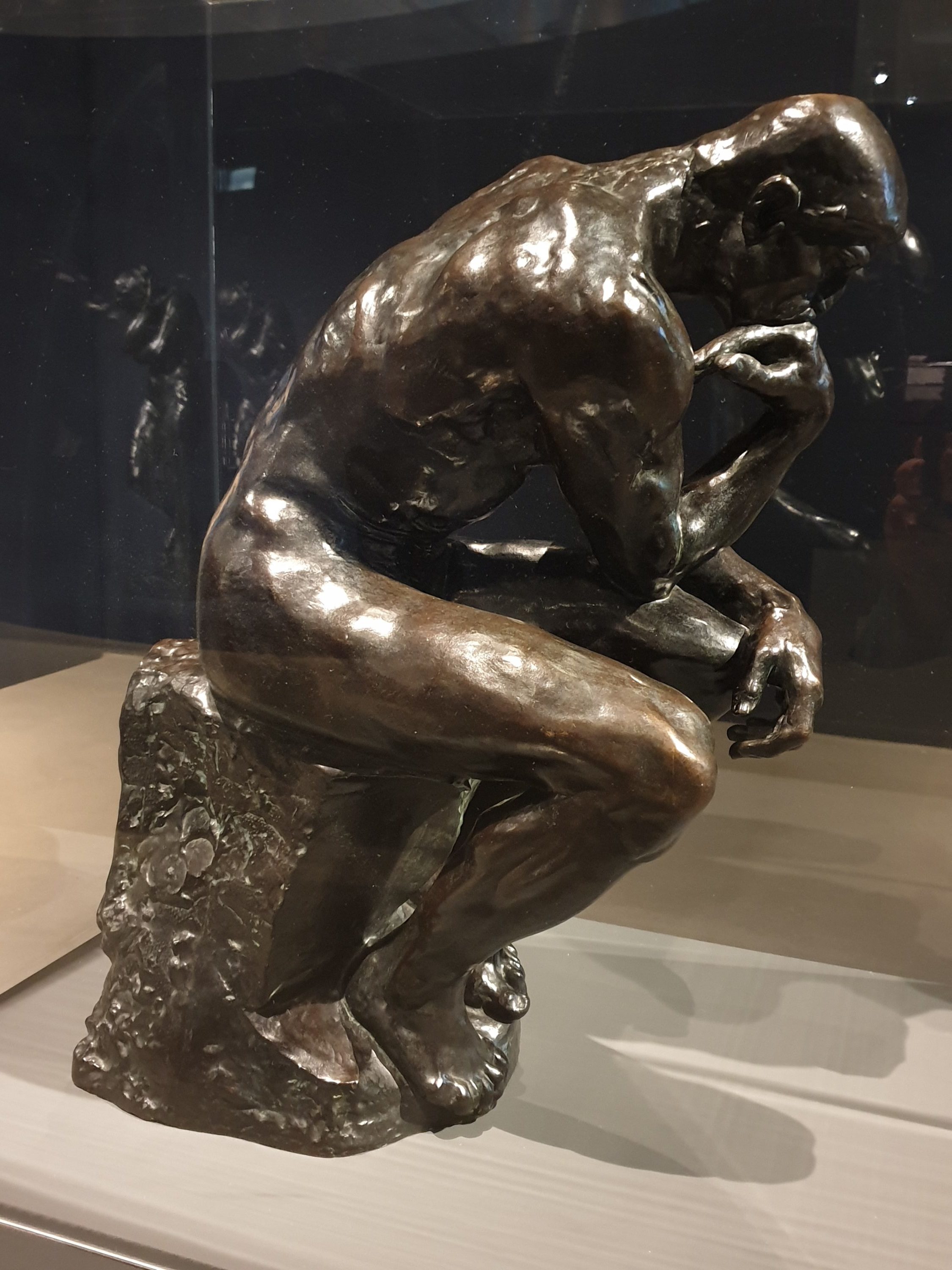

Auguste Rodin, born in Paris in 1840, obtained his craftsmanship by working as a stucco plasterer and decorator after having being refused admission to the sculpture class of the Paris Academy of Fine Arts three times. His approach to art seems to have been very intuitive and sensual, probably very much like his personality. Fascinated by the new medium of photography, the French artist, who wasn’t much of a reader, tried to capture movement, casting it in marble or bronze. He was a workaholic, who liked recombining parts of already existing works, thus revealing new contexts.

More On Lehmbruck

Lehmbruck had a much more academic upraising despite his family’s working-class background. As if he knew, that his life wouldn’t last long and more of a rationalist as a person, he quickly detached himself from every young artist’s role model of that time, Rodin. The German artist, inspired by Plato’s ideology of soul over body, worked on finding sculptural solutions for the world of ideas, leaving the depiction of naturalistic bodies behind. He stretched the body parts of his figures, thus making them thin and somehow disproportional, but strong in their contemplativeness and resignation.

All art is measurement.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck

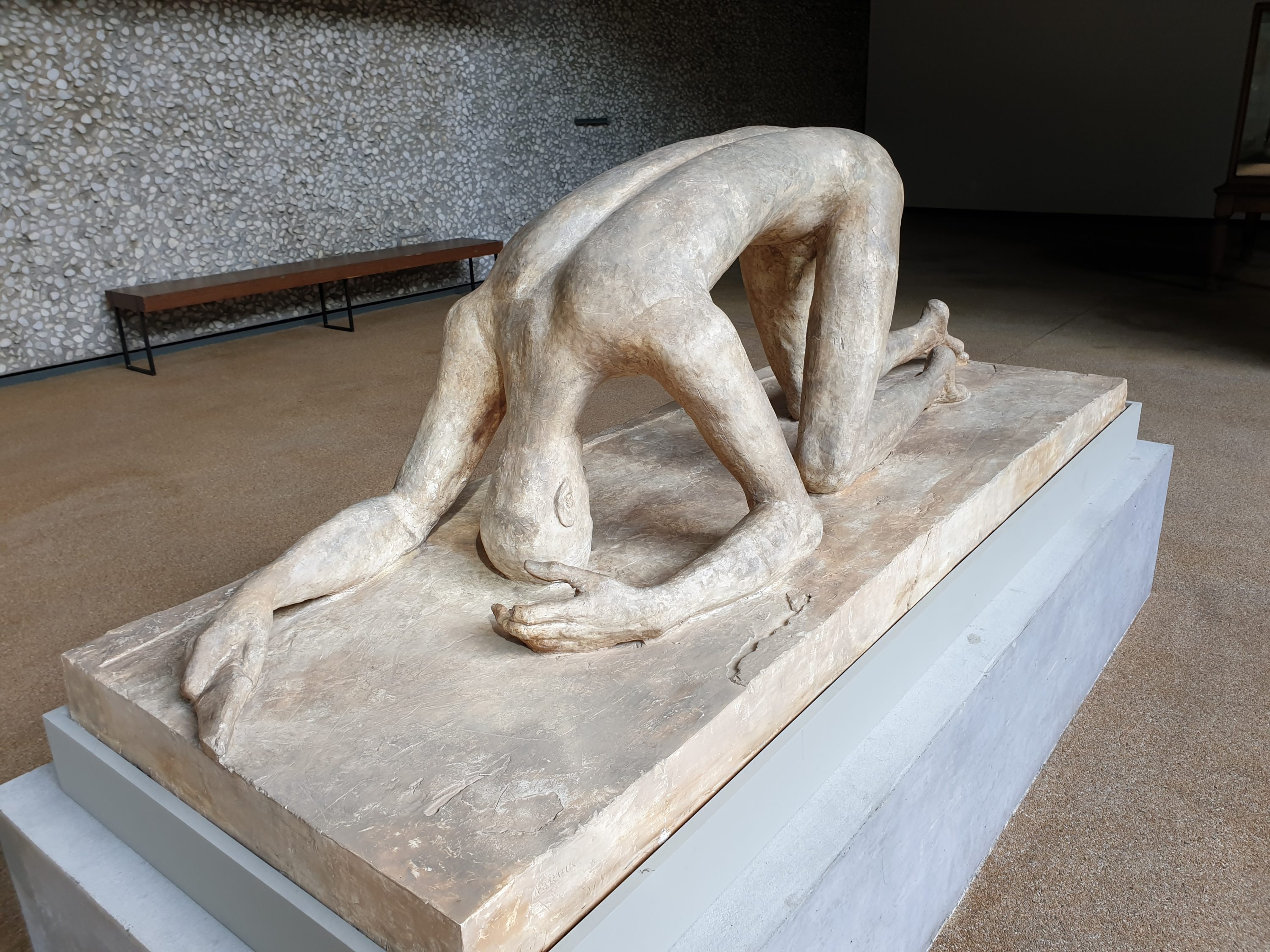

Of course, knowing that the artist put an end to his life at the early age of 38 one tends to see melancholy and sadness in his so introspective works. But shortly before and during World War I. the world seemed to be coming to an end and one can understand that a sensitive artist might not see any future. Lehmbruck expressed his feelings of despair in the poem Is There Anybody Left?, written in 1918, one year before his suicide. He had anticipated the content of this poem in his equally expressive sculpture Fallen Man in 1915 as a reaction to the city of Duisburg’s invitation to join the competition for a war memorial.

Two Very Different Thinkers

The differences between the two artists couldn’t be more obvious than in Rodin’s The Thinker and Lehmbruck’s Seated Youth, also named The Friend or The Bowed One by himself. Whereas Rodin’s famous incarnation of Dante Alighieri shows a pensive, but virile man who looks like a boxer (in fact the actual model for this sculpture was Jean Baud, a price boxer, and wrestler), Lehmbruck’s sculpture displays a young naked man, sitting with his head down in grief and despair. Once again, the anatomy is reduced, elongated and abstracted.

You see, this is my conception of a thinker. Rodin’s “penseur” is as muscular as a boxer… what we Expressionists are looking for is to precisely extract the spiritual content from our material.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck to Fritz von Unruh

The Second Impression

Just a few days after my first attendance at the Lehmbruck Museum, I visited it again. I wanted to read the explanations (which also talked about the Paris Salon and the Armory Show, the first great exhibition of modern art in the United States of America in 1913) and look at the exhibits calmly, taking time to take them in and reflect on them. Going through an exhibition on your own a second time after having taken a guided tour, rounds up the experience.

I also needed to experience this museum once again, as a whole and in each of its three wings separately. It was built in 1964 mostly as a home to the oeuvre of Wilhelm Lehmbruck by his son, Manfred Lehmbruck (1913-1991), an expert in the field of museum architecture. The part consecrated only to the works of Wilhelm Lehmbruck has a sculptural aspect itself. Build around an atrium as a central source of light, it gives the exhibited sculptures a “feeling of security”. The architect made miniature copies of his father’s works so as to be able to position them in a targeted manner in the space he created especially to showcase them. What a wonderful tribute from a son to his father.

Is this beautiful?

The Lehmbruck Museum’s exhibition entitled “Beauty. Lehmbruck & Rodin. Masters of Modernism.” opens up a dialogue between the two masters of modern sculpture. It shows how they both had a big impact on their contemporaries as well as their successors. By displaying the history-making works of Rodin and Lehmbruck in the midst of the works of their expressionism colleagues one realizes that both masters of early modernism found ways of bringing out the soul and emotion of their figures without, in most cases, completely leaving the forms of classicism. But their sculptures subtly break with the conventions and visual expectations of the late 19th century and thus point the way to modernism. The question “Is this beautiful?” goes hand in hand with subjective perception on one side, and the beauty ideal of each time period on the other, and thus remains unanswered.

My two meetings with Rodin and Lehmbruck gave me moments of beauty and contemplation. But I’d like to end this article with a personal highlight of this exhibition, Camille Claudel’s The Waltz. Like Maurice Ravel’s also La Valse entitled choreographed poem (1906-1920), it captures for me in a fascinating way the tormented spirit of the Fin de Siècle which ended in the world and art transforming Great War.