I have always wondered what makes Mona Lisa smile. Only Leonardo Da Vinci, I guess, knew why. Her smile however has always had a profound effect on me to the extent to which I could deepen my own dialogue with art and creativity in art. She, Mona Lisa, has this imperceptible pout at the cracks of her lips, which is very difficult to distinguish, between a nice grimace and a real smile. Da Vinci had devoted the last sixteen years of his life to it; perfecting an already perfect work, nuancing his own nuances, lightening up his own light to achieve the result that we all know. No matter how generous Francesco Del Giocondo was, I have no trouble believing that the finished work had by far exceeded the arrangements between him and Leonardo. You can’t really put a price tag on such a work. What is certainly true for the Joconde, is also true for any good artistic creativity. What does an artist really offer? What does the vast majority of the public really get?

What is the talent? What is its connection to art? What part does talent play in creativity?

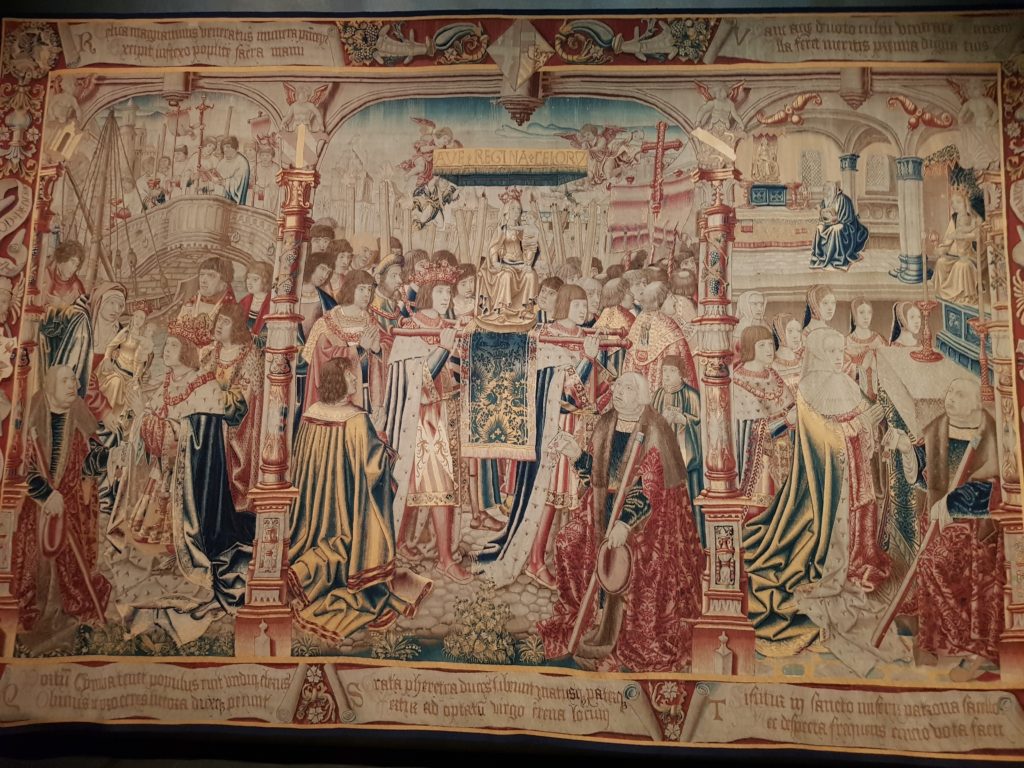

Naively perhaps, but all talent seems to me to rest on a background of generosity. Lee Scratch Perry remembers that Bob Marley was writing music for Music’s sake. Art, therefore, in that generous dimension, is what is given in a multitude of forms which varies from the sound to the light, from the thought to its plasticity under different medias. Talent thus crystallizes what is firstly given in an abstract and intuitive form to the artist, then molded from the intangible to the tangible; from the light where we have all forms of paintings, from the sound where we have all forms of music, both instrumental and vocal, from the thought where we have it, not only in the all above cited dimensions as they all involve thought, but also in all the others forms that depend on it and are made perceptible by the transformation of what was felt as an intuition to ultimately exist in various shapes.

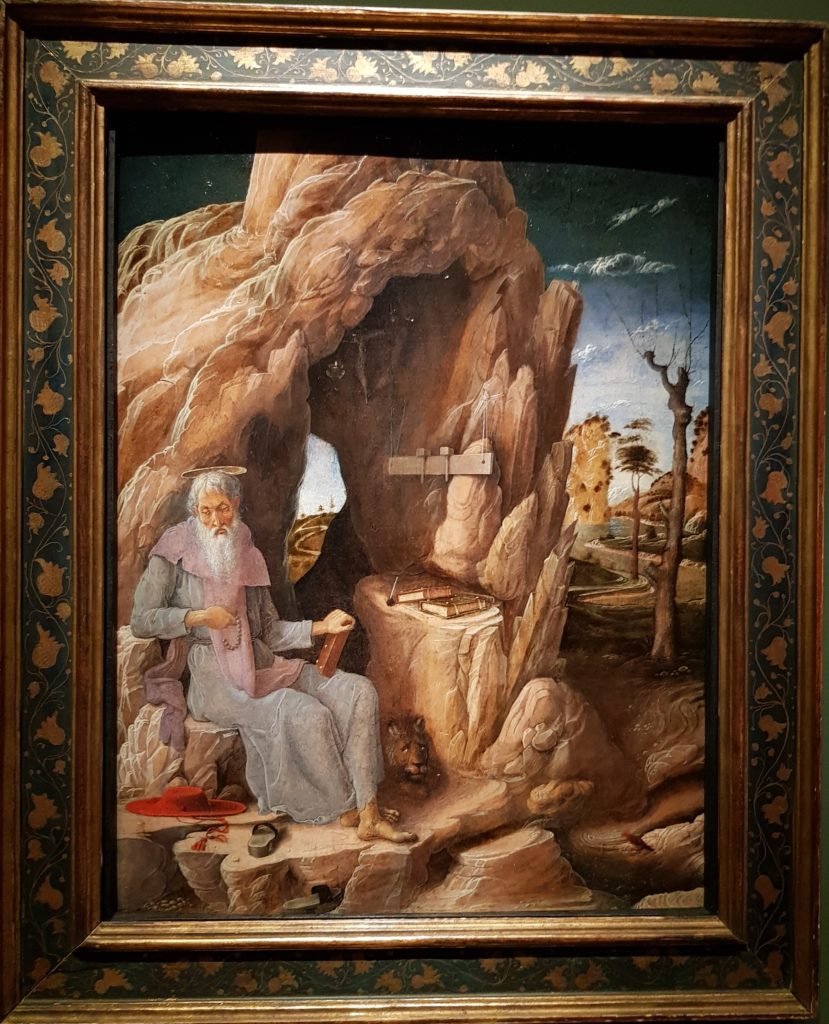

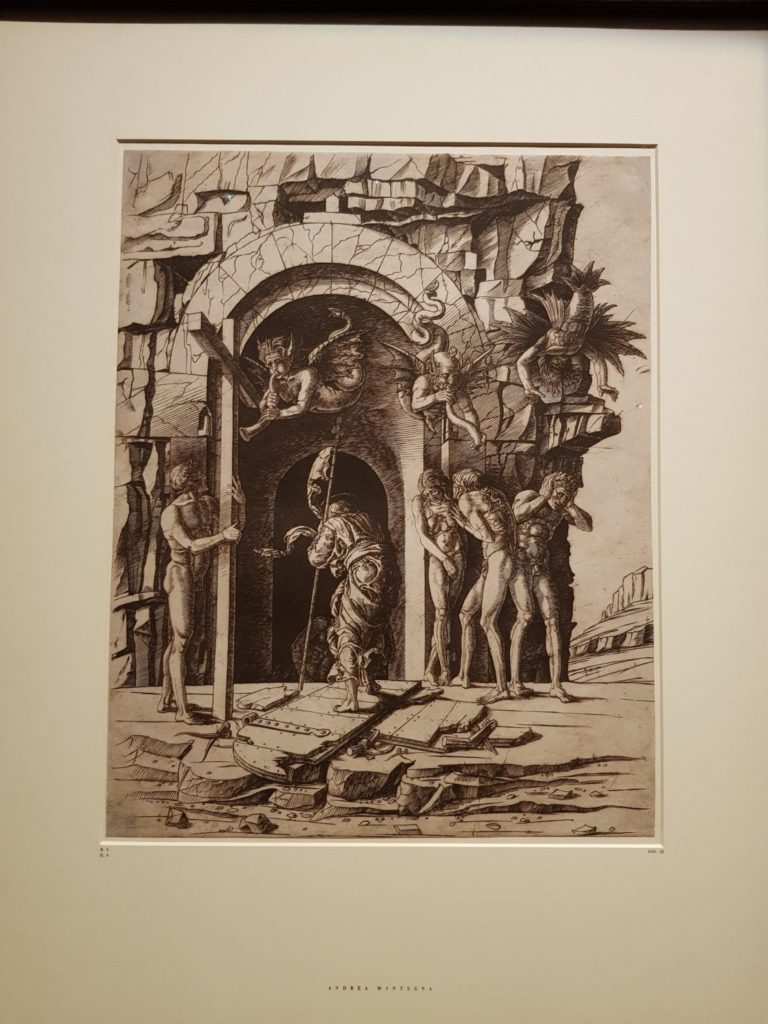

Moreover, talent is what helps to give shapes to what is given intuitively. It is therefore what manifests art through the artist. But it does not look to the artist, always to the art, looking for the one who will be the beneficiary beyond the artists themselves. There is therefore no art without a message already coded to its recipient, a message that can remain obscure even to the artist. Because they simply had the intuition or the inspiration without knowing its origin and its destination. They merely faithfully transcribed it for the one who finds some benefit in it. It is in this profound sense that we should understand the notions of generosity and talent. The artists create because that’s what his talent allows him to do. It is the brush that chooses its painter, as well as an instrument of music to the musician for an already existing message but still awaiting its messenger. There is a message in the message of art, which is possible due to the coming together of generosity and talent.

However the true reward of the artist’s talent is the recognition by their contemporaries. If the artist accomplishes themselves through their art, their art was not intended for them, but to whom receives it. If such a thing as talent exists, it is to be given. This is why we call it a gift. The artistic expression is an intimate relation between what is given through them and the one who receives it. It is precisely this relationship between the artist and the one who benefits from their art that raises the difficult question of the value of what we acquire through art. Hans Zimmer said once that at the first theatrical release of the movie Gladiator he was so moved when his wife told him that now she understood why he had been working so hard. Why had he been so difficult about the project? Because he did not want anyone, even her, to have a knowledge of what it had taken from him before it was completely finished. What does the artist offer? What does the public receive?

Going back to Mona Lisa, beyond the name of the artist, beyond the aura and the history that keep company with the painting, beyond anything that has been written or said about Lisa, as said earlier, Leonardo had worked on it the last 16 years of his life, trying to perfect it, to give to it what he thought was still in his brush. 16 years of perfecting the hand posture, the posture itself and the famous smile. That old smile, 500 years old at least but still so fresh, especially, so enigmatic… Something about that little painting of 77 cm by 53 cm seems definitely beyond its spatial and temporal frame. There is something elusive in that painting that has passed through time, which has been able to be felt since its first appearance. That thing is not determined by Lisa Gherardini or by her husband, but by what the artist felt and wanted to immortalize. That very thing is a little more than the market value to which we often in our time use to judge the value of a work of art.

With Mona Lisa, and beyond her, it is when we are in contact with a work of art of great artistic quality that the crucial question of its price arises acutely. What do we pay when we acquire a work of art? What does the artist sell when they sells a work of their hard work? What can be said of the most talented artists, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, can also be said of the work many other artists, famous or unknown. Being fair to art, we must also mention the plethora of anonymous or unknown artists in its annals, especially in baroque music, where we find radiant works without a name to claim them. Or others artists, who have only one major work to their credit, as Johannes Pachelbel and the majority of those who are still waiting in this life or posthumously that their work finally finds the audience for which it was intended . . .

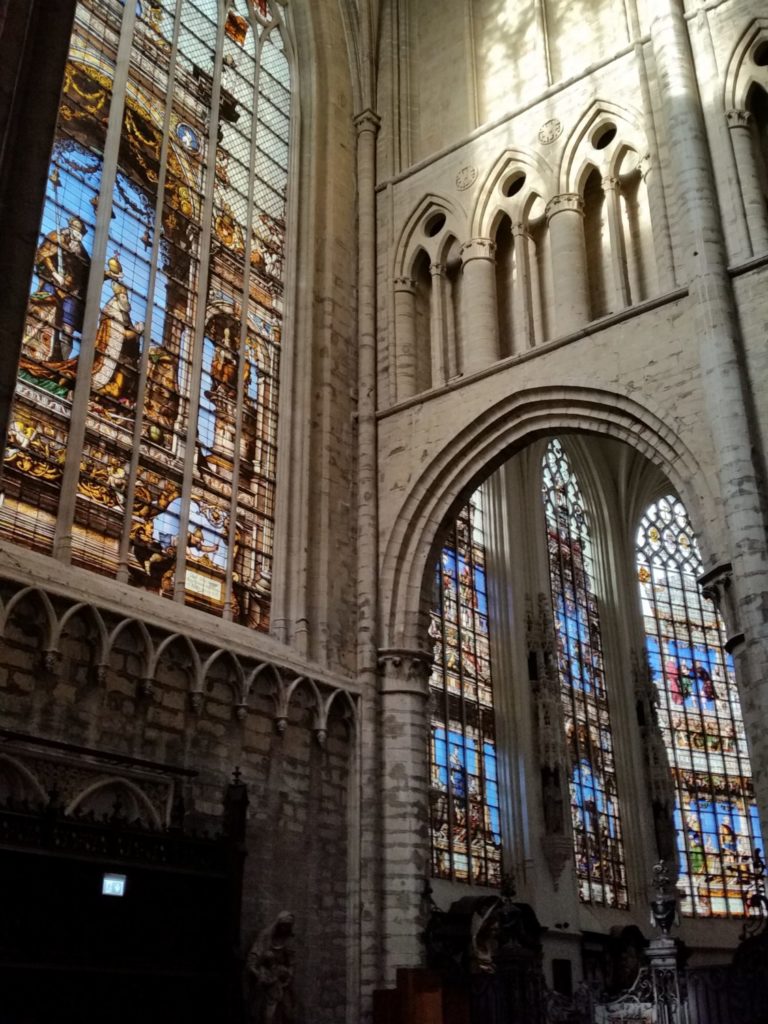

The artist creates for art. But the art itself implies an audience to receive it. Art thus unites the artist and their audience. Talent and beauty by nourishing the artist have no other price than to let the art exists for all eternities. The artist creates for immortality. The tendency to blend the art and the notion of immortality is much older than Rome and even ancient Greece. The art has always had something very spiritual and divine. This is the ultimate price for which the artist sacrifices everything. The art is the expression of the deep quest for beauty of the human spirit, it highlights the harmonies, the tensions, the wanderings, the moments of calm of the universe itself in the soul of a Beethoven, a Miron ,an Imothep, a Fela Kuti, an André Brink, a Bertone (if an automobile can be conceived as a piece of art), etc. The artists offer in their work the profound experience of the many universes in motion within them. The public acquires in material form that expression which is revealed in snippets, by the crumbling and the sweating so to speak of the meaning contained within each work of art that takes sometimes several generations of enthusiasts to appreciate it without ever exhausting its content.